The question of whether one’s artistic expressions can be be used against one in a criminal trial occurs with some frequency. This is not about being criminally prosecuted for the expression itself, as in an obscenity case. Instead, this is about using artistic expression as evidence to prove that a defendant’s intent or motive to commit the crime.

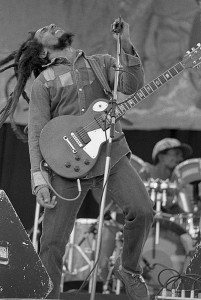

In such scenarios, Bob Marley’s well known song “I shot the sheriff” could be used at trial if he had been prosecuted for murder of a law enforcement officer. And Johnny Cash’s famous lyric “I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die,” could be introduced at trial if he had been prosecuted for first degree murder, presumably even if not in Reno, to show his bad intent.

In such scenarios, Bob Marley’s well known song “I shot the sheriff” could be used at trial if he had been prosecuted for murder of a law enforcement officer. And Johnny Cash’s famous lyric “I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die,” could be introduced at trial if he had been prosecuted for first degree murder, presumably even if not in Reno, to show his bad intent.

In State v. Skinner, the New Jersey Supreme Court reversed the introduction of rap lyrics authored by the defendant before the alleged crime. The court interpreted the commonplace evidentiary rule that requires a weighing of the “prejudicial impact” of evidence against its “probative value.” The lyrics were deemed prejudicial because they were violent and obscene. But the more important query was whether they were at all “probative”? Which brought the court to Bob Marley, as well as to Edgar Allen Poe:

The difficulty in identifying probative value in fictional or other forms of artistic self-expressive endeavors is that one cannot presume that, simply because an author has chosen to write about certain topics, he or she has acted in accordance with those views. One would not presume that Bob Marley, who wrote the well-known song “I Shot the Sheriff,” actually shot a sheriff, or that Edgar Allan Poe buried a man beneath his floorboards, as depicted in his short story “The Tell-Tale Heart,” simply because of their respective artistic endeavors on those subjects. Defendant’s lyrics should receive no different treatment. In sum, we reject the proposition that probative evidence about a charged offense can be found in an individual’s artistic endeavors absent a strong nexus between specific details of the artistic composition and the circumstances of the offense for which the evidence is being adduced.

The opinion is decidedly grounded in the rules of evidence that govern criminal (and civil) trials rather than the First Amendment, but First Amendment protections for free expression cast a long shadow here. The New Jersey Supreme Court’s unanimous opinion contains a lengthy passage describing the First Amendment discussion in the ALCU’s amicus brief, although the court never explicitly returns to the First Amendment in its own analysis. The “nexus” language is key. To the extent that expression details the accused crime, it is more likely to be admissible. But the New Jersey Supreme Court makes clear that a song about how one shot the sheriff (and not the deputy) isn’t likely to be admitted in a criminal trial to prove your intent to commit murder.

[image via; more discussion on the Constitutional Law Professors Blog here].