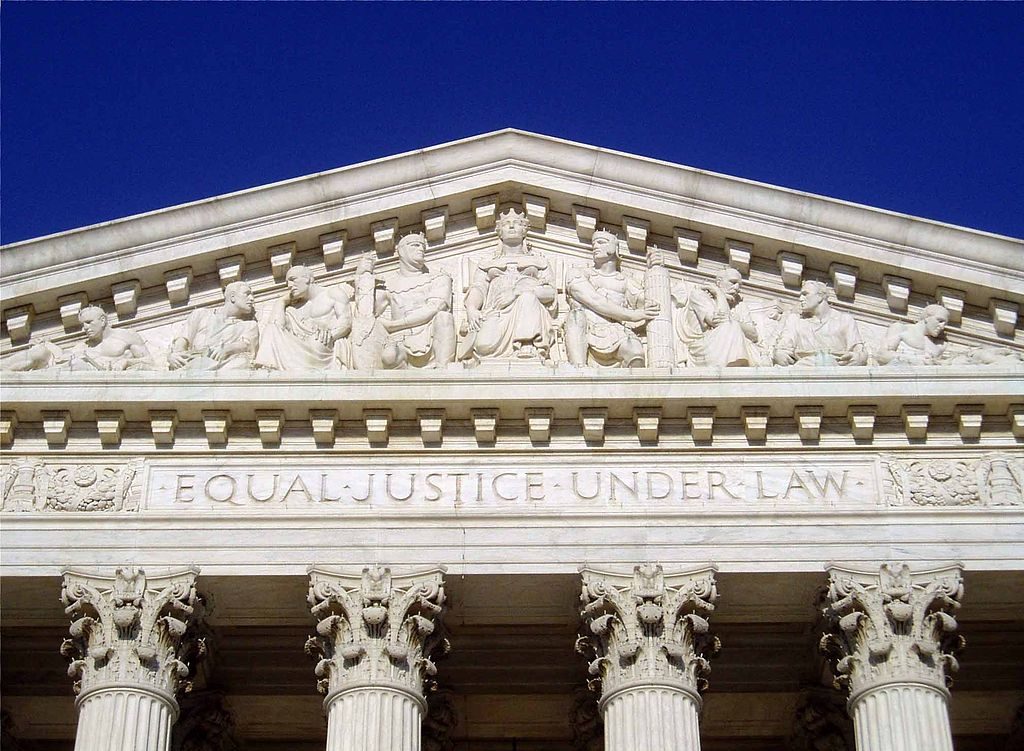

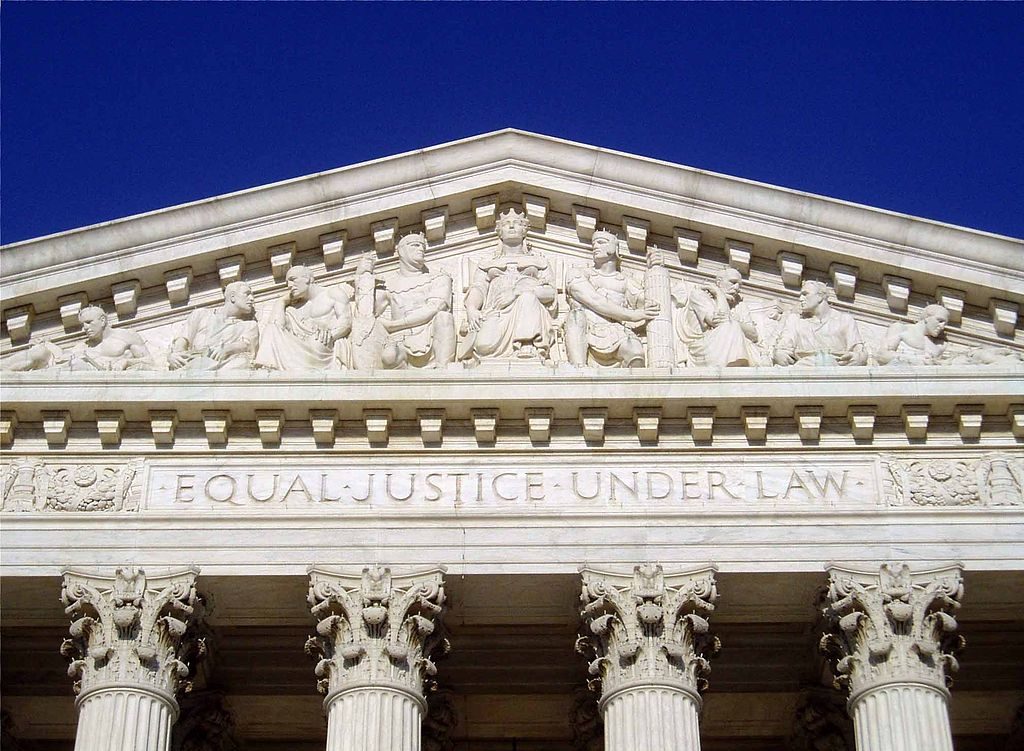

The United States Supreme Court hears only small fraction of cases: The Court hears about 80 cases a year, of the approximately 8,000 requests for review filed with the Court each year, flowing from the approximately 60, 000 circuit court of appeals decisions and many more thousands of state appellate court opinions. And of this small fraction, generally about half involve constitutional issues, including constitutional criminal procedure issues.

The United States Supreme Court hears only small fraction of cases: The Court hears about 80 cases a year, of the approximately 8,000 requests for review filed with the Court each year, flowing from the approximately 60, 000 circuit court of appeals decisions and many more thousands of state appellate court opinions. And of this small fraction, generally about half involve constitutional issues, including constitutional criminal procedure issues.

Not surprisingly then, with the new Term starting October 3, the traditional first Monday in October, there are only a handful of constitutional law cases included among the less than 30 the Court has already accepted.

The CUNY Law Review will be holding an event Thursday, September 29, 2016 at 6pm at the law school with professors discussing the new Term. More info here.

Here’s a quick rundown of the questions the Court will be considering with more detail over at the Constitutional Law Professors blog.

Can – – – or how can – – – a state legislature redistrict the state and take into account racial demographics? The Court is set to hear two racial gerrymandering cases, both of which involve the tensions between the Voting Rights Act and the Equal Protection Clause with underlying political contentions that Republican state legislators acted to reduce the strength of Black voters; both are appeals from divided opinions from three-judge courts. In Bethune-Hill v. Virginia State Board of Elections, the challenge is a lower court finding that a number of Virginia House of Delegates districts did not constitute unlawful racial gerrymanders in violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. In McCrory v. Harris, a racial gerrymandering case involving North Carolina, the challenge is to a three-judge court’s decision finding a constitutional Equal Protection Clause violation.

In another Equal Protection Clause case, the question involves sex discrimination by the United States in its immigration law. In Lynch v. Morales-Santana, the underlying problem is differential requirements regarding US presence for unwed fathers and unwed mothers to transmit citizenship to their child; the Second Circuit held that the sex discrimination was unconstitutional, subjecting it to intermediate scrutiny under equal protection.

Are religious organizations entitled to be treated “equally”? Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Mo. v. Pauley also includes an Equal Protection issue, but the major tension is between the Free Exercise of Religion Clause of the First Amendment and principles of anti-Establishment of Religion. Like several other states, Missouri has a so-called Blaine Amendment in its state constitution which prohibits any state monies being used in aid of any religious entity. Missouri had a program for state funds to be awarded to resurface playgrounds with used tires; the state denied the Trinity Lutheran Church preschool’s application based on the state constitutional provision; the Eighth Circuit sided with the state of Missouri.

There are also several cases involving the criminal procedure protections in the Constitution. Pena-Rodriguez v. Colorado involves a claim of racial bias on a jury in a criminal case. The Colorado Supreme Court resolved the tension between the “secrecy of jury deliberations” and the Sixth Amendment right to an impartial jury in favor of the former interest. The court found that the state evidence rule, 606(B) (similar to the federal rule), prohibiting juror testimony with some exceptions was not unconstitutional applied to exclude evidence of racial bias on the part of a juror. Bravo-Fernandez v. United States involves the protection against “double jeopardy” and the effect of a vacated (unconstitutional) conviction. It will be argued in the first week of October. Moore v. Texas is based on the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment, with specific attention to capital punishment and the execution of the mentally disabled. In short: what are the proper standards for states to make a determination of mental disability?

Finally – – – at least for now – – – the Court will also be hearing a constitutional property dispute. Murr v. Wisconsin involves the Fifth Amendment’s “Taking Clause,” providing that private property cannot be “taken” for public use without just compensation. At issue in Murr is regulatory taking. The Court granted certiorari to a Wisconsin appellate court decision regarding two parcels of land that the Murrs owned since 1995; one lot had previously been owned by their parents. Under state and local law, the two lots merged. The Murrs sought a variance to sell off one of the lots as a buildable lot, which was denied. The Murrs now claim that the denial of the variance is an unconstitutional regulatory taking. The Wisconsin courts viewed the two lots as the “property” and concluded that there was no regulatory taking.

Look for updates as the Court adds more cases to its docket.

The Memo does raise several other possibilities, including one under the 25th Amendment involving the Vice-President, as well as the legislative actions. The Memo, by Mary Lawton, was dated August 5, 1974; Nixon resigned a few days later. A month later, President Gerald Ford issued a Proclamation with a full pardon to Nixon.

The Memo does raise several other possibilities, including one under the 25th Amendment involving the Vice-President, as well as the legislative actions. The Memo, by Mary Lawton, was dated August 5, 1974; Nixon resigned a few days later. A month later, President Gerald Ford issued a Proclamation with a full pardon to Nixon.