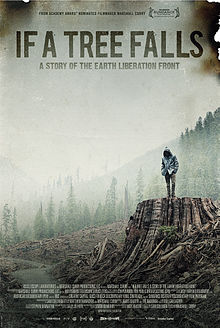

Maybe you’ve heard of Daniel McGowan? He’s well known as an environmental activist who lives in Brooklyn and featured prominently in the 2011 documentary, If a Tree Falls: A Story of the Earth Liberation Front.

He went to federal prison for arson in connection with his “activities,” but gained transfer to the Brooklyn House Residential Reentry Center (“RRC”) near the end of his sentence with work passes and other privileges. While at RCC in April 2013, McGowan published an article on Huffington Post entitled “Court Documents Prove I was Sent to Communication Management Units (CMU) for my Political Speech.”

He went to federal prison for arson in connection with his “activities,” but gained transfer to the Brooklyn House Residential Reentry Center (“RRC”) near the end of his sentence with work passes and other privileges. While at RCC in April 2013, McGowan published an article on Huffington Post entitled “Court Documents Prove I was Sent to Communication Management Units (CMU) for my Political Speech.”

Interestingly enough, the publication of this article about being disciplined for political speech caused McGowan to be disciplined. The RCC manager to essentially revoke the RRC status and remand McGowan back to the Bureau of Prisons – – – in solitary confinement – – – for an infraction of a regulation that provided “an inmate currently confined in an institution may not be employed or act as a reporter or publish under a byline.”

If that “byline regulation” sounds as if it might be a violation of the First Amendment, it is. It was challenged and a federal district judge in Colorado in 2007 ruled that it was. The Bureau of Prisons (BOP) did not appeal, and in fact the BOP instructed staff not to enforce it. In 2010, the BOP issued an interim regulation rescinding the byline regulation; in 2012 it issued the final rule.

McGowan was lucky; he had lawyers who soon figured out the byline regulation under which he had been charged was no longer in force and McGowan was returned to the RRC.

But McGowan sued the RCC personnel for a violation of the First Amendment. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals, affirming the district judge, rejected the claim in its opinion in McGowan v. United States, concluding that the BOP was insulated by qualified immunity. Qualified immunity protects the government from liability for violation of a constitutional right unless that right was “clearly established” at the time of the violation. Here, despite the conclusion of a district judge six years prior that the byline regulation was unconstitutional and the rescission of the byline regulation by the BOP, the Second Circuit held that the right the byline regulation infringed was not clearly established:

We conclude that, at the time the alleged violation occurred, our case law did not clearly establish that McGowan had a First Amendment right to publish his article. The Supreme Court has held that “when a prison regulation impinges on inmates’ constitutional rights, the regulation is valid if it is reasonably related to legitimate penological interests.” Turner v. Safley, 482 U.S. 78, 89 (1987)). This test is “particularly deferential to the informed discretion of corrections officials” where “accommodation of an asserted right will have a significant ‘ripple effect’ on fellow inmates or on prison staff.” Id. at 90. For example, the Supreme Court has upheld “proscriptions of media interviews with individual inmates, prohibitions on the activities of a prisoners’ labor union, and restrictions on inmate‐to‐inmate written correspondence.” Shaw v. Murphy, 532 U.S. 223, 229 (2001) (citations omitted).

In short, the ” only authority that McGowan has identified that involved expression similar to that at issue in this case is a district court opinion, which, of course, is not binding.” The court also rejected claims sounding in tort regarding the BOP’s failure to follow its own regulations.

So McGowan has no remedy for the BOP enforcing a rescinded and it seems unconstitutional regulation that caused his removal from a work program to solitary confinement.

If a tree falls . . . .